|

A Gawliwada community member in Naydongri

village in Nashik. The clan of buffalo herders needs 50,000 litres of water for

its animals every day in this village. (Express Photo/Nirmal Harindran)

|

In Naydongri village in Nashik’s Nandgaon taluka, water scarcity in the

summer months is an annual worry, but in the over five decades that the

Gawliwada or community of buffalo herders has been here, distress migration has

never been a concern. After all, with 1,800 to 2,000 water buffaloes to care

for, the Gawli clan of Naydongri cannot very well relocate at will. This year,

however, with summer still four months away and acute water scarcity settling

in already, Shankar Umaji Namde, 60, is in talks with landowners in Niphad, nearly

100 km away, to locate an alternative site for their animals. They plan to

leave the children behind in the care of the elderly to make sure a school year

is not lost. Some younger women will stay back too. The men will look to

quickly establish the market linkages crucial to their business.

“Families will be split, all manner of other problems will arise, not to

mention that it will be a year of deep losses,” says Namde, a sunburnt man who

greets visitors to his home with piping hot cups of fresh, creamy milk. “But

there’s already no water, how will we manage when March-April comes around?”

For now, the Naydongri sarpanch and gram panchayat have asked them to

stay back, but arranging the 50,000 litres of water that the animals need every

day seems implausible.

|

In the over five decades that the community

has been here, distress migration has never been a concern. (Express

Photo/Nirmal Harindran)

|

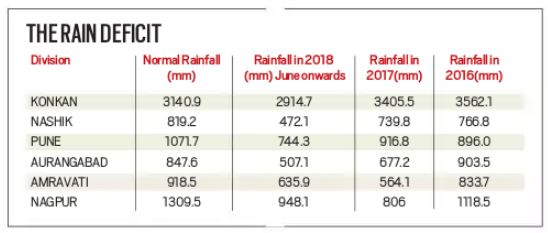

Overall this year rainfall in Maharashtra is about 30 per cent lower than

the 1210.8 mm average annual precipitation. On October 24, Chief Minister

Devendra Fadnavis admitted that nearly half of the state (180 of 350 talukas)

was drought-hit. Districts in Marathwada (deficit of 36.6 per cent) and Nashik

district (deficit of 39.4 per cent) are the worst affected. Along with water

scarcity as early as November has come the foreboding of a scorching summer

ahead. And with rabi crop (sown in October-December) set to hit all-time low in

the drought-hit districts, communities that do not traditionally migrate for

work have begun to do so.

For many of these 180 talukas,

cyclical drought is a complex reality. While 2017 saw above average rains

almost across the state, many talukas are currently facing their third drought

in the last six years.

Samba Aushikar and his father

Sathva are wary of the cost of transportation — a truck for their 30 water

buffaloes will cost Rs 50,000 for the one-way trip. Additionally, there’s no

clarity if their average daily sale of 200 litres of milk will fetch decent

prices in the new location. “We’ll have to sell at whatever rate offered. It’s

not like we can store our produce,” says Samba, who will leave his children

behind with mother Avadabai. The 65-year-old Avadabai, who has never lived

alone, adds, “It’s going to be a terrible summer, and we’ll have to manage

without our animals or our sons around.”

Next door, the three sons of

Devkibai Nistani, 66, are planning to make the shift. Like most others in the

Gawliwada community, they have been spending Rs 600 a day for a 3,000-litre

water tanker, much lesser than the 5,000 litres their 35 buffaloes need. By

January the tankers will be tougher to get, and more expensive. “We are left

with no choice but to move, we just need to keep the animals alive, get by

somehow in the hope of a better year later,” Nistani says, adding that she will

stay back to look after the children.

“Our animals’ dung will have to

be given for free to the landowner as fertiliser, and I expect I’ll have to

work on somebody’s farm to earn fodder. But what option do we have?” asks Shidu

Nistani, 30, her son.

|

Overall this year

rainfall in Maharashtra is about 30 per cent lower than the 1210.8 mm average

annual precipitation. (Express Photo/Nirmal Harindran)

|

Over 300 km away in the heart of

Marathwada, after the failure of his 2.5 acres of cotton crop, Balasaheb Anuse,

58, has taken up work as a sugarcane harvester. The villager from Rewali in

Parli taluka of Beed district made the journey to Latur’s Natural Sugar and

Allied Industries in Kalamb taluka, Osmanabad. “The severe water scarcity in

Beed ruled out a rabi crop. This was the only way to earn a living,” says the

farmer whose wife, son and daughter-in-law have also travelled with him. Anuse

has joined the band of cane harvesters after almost 20 years.

Across Marathwada, many small

land holders like Anuse have swelled the ranks of migratory cane harvesters.

Usually, around seven-eight lakh migrant workers, mainly from Beed, Ahmednagar

and parts of Nashik, go to mills in Maharashtra, Karnataka, Gujarat and Madhya

Pradesh. Pre-booked by mills, they are paid through labour contractors on a

fixed rate per tonne of cane harvested. This year, sugar mills in Maharashtra

say they are flush with excess harvesters.

Bhairavnath B Thombare, chairman

and managing director of Natural Sugar and Allied Industries, says 10,000

labourers have turned up, twice the usual number. “In many cases labourers have

come without the advance,” he says. Ironically, just last year, sugar mills in

the state had faced a paucity of such labourers in view of better water

availability in their villages and therefore farmlands to tend.

In Jalna’s Bhokardan taluka, over

the past few weeks, trucks loaded with harvesters have been leaving villages.

Kamlakar Pachunde’s son and two nephews, from Pimpalgaon village, were among

those to leave. Nobody in their family went last year, or the year before, says

Pachunde, who is in his late sixties.

In Manmodi village in Beed’s

Georai taluka, 90 per cent of the able-bodied men and women have left for

harvesting work. Arun Yewle, chairman of the village’s primary agricultural

cooperative society, says in earlier years, the average of such migration was

25 per cent.

In Aurangabad’s Khultabad taluka,

many are moving to nearby Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC)

units. In Kanadgaon and Mahmadpur villages here, 400 have found work in the

Waluj MIDC, including 50 who have moved out to live in rented accommodation on the

outskirts of Aurangabad. Another 50 are at sugar factories.

Baban Chavan, a landless labourer

from Naigaon village in Kalamb taluka of Osmanbad, will relocate to Pune by the

end of November. Ten to 15 families of his hamlet are planning to similarly

move, to either Latur or Pune. Subhash Rasal and his wife Vrindavani are

skilled masons, but there’s no work in the village. “Farmers have no work for

us,” says Rasal, who’s worried about not being able to pay his son’s fees.

Across the region, district

collectors claim they are readying ample work to offer under the MGNREGS.

Osmanabad Collector R B Game says 42 lakh man days of work are ready and the

administration is prepared to extend the availability of work beyond the

100-day mandate.

But in village after village,

landless labourers as well as small and marginal farmers say while demands have

been made through gram panchayats for MGNREGS work, they’re still to hear from

local officials. Meanwhile, the migration continues. Underlining that it is not

to improve their economic status, livestock herder Namde says, “There’s loss in

both leaving and in staying, but migrating ensures survival.”

Source:https://indianexpress.com/article/india/parched-villages-begin-to-empty-out-in-drought-hit-maharashtra-5456398/

No comments:

Post a Comment