Bhanu Prakash Chandra

Bhanu Prakash Chandra

Six-year-old Bengaluru schoolgirl Jia woke up on the morning of September 7 to see Prime Minister Narendra Modi consoling ISRO chairperson K. Sivan with an embrace on television. She had learnt in school that India was going to land on the moon while she slept. Clearly, something had gone wrong. So we failed, she exclaimed. Her mother consoled her, saying the story does not have a very sad ending, and there is a thick silver lining. Most importantly, the mother realised she could not be indifferent to the subject, but should learn everything about Chandrayaan-2, because clearly, rocket science is the trending topic.

India’s second lunar probe, Chandrayaan-2, aimed to land and walk on the moon, hoping to make history by being the first country to explore its south pole and the first to manage a soft landing in its maiden attempt. One mission objective was “to surpass international aspirations”. The ambition was big, the stakes high, the probability not much in favour. The attempt failed. The earth station lost signal with the probe, Vikram, just 2.1km above its destination. It crashed very close to where it was hoped to have landed elegantly, like a cat, on four feet.

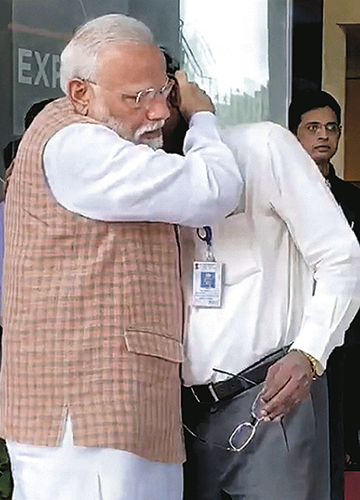

The disappointment was so crushing that the stoic chairman—who had earlier told THE WEEK that failure and success were part of the game—teared up and Modi had to stretch out his arms in that famous “jaadoo ki jhappi”, assuring both Sivan and the country that the attempt was laudable, the journey was jaandaar (robust) and shaandaar (impressive), and so what if Vikram could not control itself in the last leg but rushed to meet the moon.

Sivan recovered enough composure by evening to announce that the mission was 95 per cent successful. The orbiter, with eight payloads, was working well and could outlive its mission life of a year by another six, given its fuel reserves.

Subsequently, Vikram was sighted by the orbiter, but it appears to be facing away from the earth. So neither ISRO nor NASA can “hear” it yet. The attempt is now to talk to it through the orbiter, which may be lowered from its 100km orbit. There is time till September 20, the planned mission life, after which Vikram’s solar-powered batteries will drain away.

Chandrayaan-2 had set out on an ambitious ride. Apart from technology demonstration, scientific goals and international posturing, the mission had another aim, too. It reads: To inspire a future generation of scientists, engineers and explorers. There can be little doubt on the success on this front. Chandrayaan-2 has fired the interest of a nation in a way no other space mission managed before. In fact, the unfortunate end of Vikram has made rocket science more relatable to people. From preschools to post-retirement circles, discussions are around what went wrong, what next and why it matters. Fewer people are questioning why India should go to the moon when its roads are pockmarked and bellies empty. Because, now they know why. Orbiter, lander and rover are no longer incomprehensible terms, but part of the national lexicon.

Chandrayaan-2 was conceived in the rosy afterglow of India’s first successful moon jaunt in 2008. Back then, it was to be jointly parented with Russia’s space agency Roscosmos, which was to provide a lander while India worked on the orbiter and rover. But in November 2011, Russia sent a spacecraft to Phobos, a martian moon, to return with soil samples. The Fobos-Grunt flight never left the earth’s orbit, crashing into the Pacific Ocean two months later. A shaken Roscosmos decided to review all future missions. Chandrayaan-2’s lander was similar to the one that was being sent to Phobos, and Russia said it could not provide India the lander in time.

ISRO saw opportunity in the setback to develop an indigenous lander from scratch. It was only by 2018 that India had a good prototype. The lander was fitted with four 800N engines, developed indigenously, to apply brakes during landing. But during trials, the landing was a dusty affair, not conducive to the health of sensitive scientific equipment. So, they added a central engine that would fire up closer to landing when others turned off. Meanwhile, the scope of the mission expanded—the orbiter was already packed with eight payloads, even NASA was sending an instrument. The delay helped. India finally got success with a heavier launch vehicle, the maverick GSLV and last year, was able to transfer the mission to the largest car in ISRO’s garage, the mighty GSLV Mk-III, aka Bahubali.

Since 2018, launch was repeatedly rescheduled, as ISRO kept testing the technology. This April, during trial, the lander fell and damaged a leg. In retrospect, should ISRO have tested it more? “No. ISRO’s review system is thorough. It took care of all foreseeable possibilites. In space science, there are many unknowns,” said retired Group Captain Ajay Lele, senior fellow,

Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses.

Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses.

Sivan was well aware of the odds, as he often spoke about the last “15 minutes of terror”. India had twice before demonstrated capability of leaving earth’s orbit, travelling across deep space and inserting into another orbit, with the moon and Mars voyages. A soft landing was a first. China’s mission to the dark side of the moon succeeded only after previous faulty landings. This April, Israel’s Beresheet lost contact with its earth handler 10km above surface.

By that standard, India was able to demonstrate a successful rough braking phase (deceleration from 1,680mps at 30km altitude to 146mps at 7.4 km altitude). This means that its four 800N thrusters worked well. The first 10 of those 15 terror-prone minutes were nail-biting, but ended in applause. Even the 38-second absolute navigation phase went well. This is now proven technology for ISRO, and will be useful in planning future missions, said Rajendra Prasad of Exseed Space, a private commercial space organisation.

During transition to the fine braking phase, when the central engine should have taken over, something went wrong and ISRO lost contact. Vikram needed to slow down to near zero. It also had to straighten its horizontally stretched legs to point downwards for landing. It was still at a speed of 48.59mps when the signal was lost. Prima facie, sources say, it looks like an engine failure, which could not curb the speed.

Given that the mission control centre of ISRO Telemetry, Tracking and Command Network (ISTRAC) was literally on reality television for a global viewership, every expression of the scientists and technicians hunched over their consoles was visible to the public. It took only seconds for both scientists and the lay public to realise that something was amiss. As the minutes ticked by, the air thickened with tension. When the announcer said, “Sixteen minutes, 18 seconds [since commencing deceleration],” everyone knew the terror was real. That the end would be sad.

Apart from Modi, the invited audience included schoolchildren from India and Bhutan, former ISRO heads K. Radhakrishnan, K. Kasturirangan and A.S. Kiran Kumar, and K. VijayRaghavan, principal scientific adviser to the government. Sivan strode over to talk to Modi, who had dressed for the occasion in a black-and-white waistcoat. Modi absorbed the bad news and said, “Hope for the best, you have done good work.”

When Sivan returned and mumbled that communication from lander to ground station was lost at an altitude of 2.1km from the surface, it was like hearing the doctor announce the death of a dear one. As the heat of enthusiasm ebbed, the chill of that September air hit, while a half moon gazed down.

“These things happen in the scientific world. In an individual experiment, the disappointment is personal; in collective research, the group gets dismayed at failure. In a national mission, the entire country feels disappointed,” said VijayRaghavan.

Like every space mission, this is not ISRO’s first “failure”. Right from the time Aryabhata, India’s first satellite, lost contact four days after launch, success has come peppered with disappointments. Even ISRO’s rockstar, the PSLV rocket, after 24 years of sincere service, had one bad flight in 2017, when its heat shields, which protect the satellite during takeoff, did not open up. Last year, ISRO lost a satellite, GSAT-6A, three days after launch.

Those incidents, and the slew of GSLV failed flights over the past two decades, were talked of in scientific circles, but did not blip much on public consciousness. Chandrayaan-2 was different. Heady on a string of successes—discovering water on the moon, a successful martian mission that rode on a slender PSLV, and the record-breaking carriage of 104 small satellites into orbit—space is no longer a remote subject for Indians. The film Mission Mangal has made rocket science appear as simple as frying puris. It is a sobering thought that where there is success, there can be failure.

ISRO itself has become approachable and interactive. It ran contests on social media. So while the stars of previous missions remained anonymous till the applause, Chandrayaan-2’s people and payloads are known names. The lander was named after Vikram Sarabhai, the rover Pragyan after the Sanskrit word for wisdom, thus imbuing even machines with personalities. Publicity is a double-edged sword, though. And the disappointing end of the flight could not be insulated from public glare. It got sympathy and empathy. The risk now is that space science is falling victim to jingoism, which could be worse than indifference.

In the emotional response to Vikram’s crash, an important takeaway of the mission got obscured. This was the GSLV Mk-III’s first operational flight, and it is now a proven vehicle that can carry a four-tonne payload. Given that it took two decades to develop the cryogenic technology, this by itself calls for popping the champagne. The launch was initially aborted at eleventh hour on July 15, because of a technical snag, which was rectified in days. That again, is proof that ISRO is in sync with the moods of the vehicle.

The orbiter has the most powerful camera (0.3m resolution) in any lunar mission. Its instruments will help in understanding the evolution of the moon and mapping of minerals and water molecules in the south polar region. Vikram, even with a disappointing landing, has “proven variable thrust propulsion technology”.

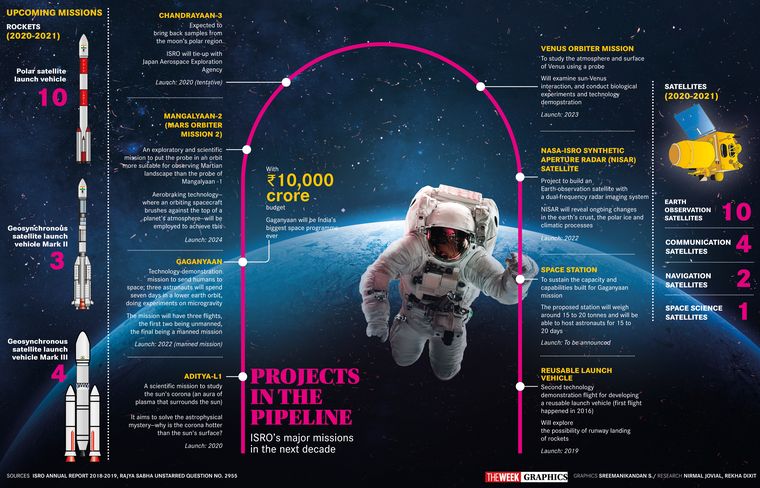

There is as little time or luxury to lick wounds as there would have been to bask in glory. The schedule ahead is challenging and packed with the big-ticket launch of the scientific probe Aditya, to study the sun’s corona. ISRO’s small space launch vehicle (SSLV), designed for launching small and micro satellites, should fly soon. Gaganyaan is under way and ten Indian Air Force pilots have been shortlisted for astronauts. An Indian space station is in the offing. Japan, which has proven sturdy legs for landing, reaffirmed its tie up for a moon revisit in the early 2020s. A second Mars mission and a Venus voyage are also planned.

There is also the routine work of launching communication and navigation and commercial satellites. Last year, ISRO had 17 missions; 32 were planned for this year, though the moon date has reshuffled the launch calendar considerably.

The moon will continue revolving around the earth, and Chandrayaan-2’s orbiter around the moon. And for many moons to come, as Indians look skywards, they will think of Vikram, crouched on the south pole, fractured and forlorn. This tragedy will always be a personal one.

No comments:

Post a Comment